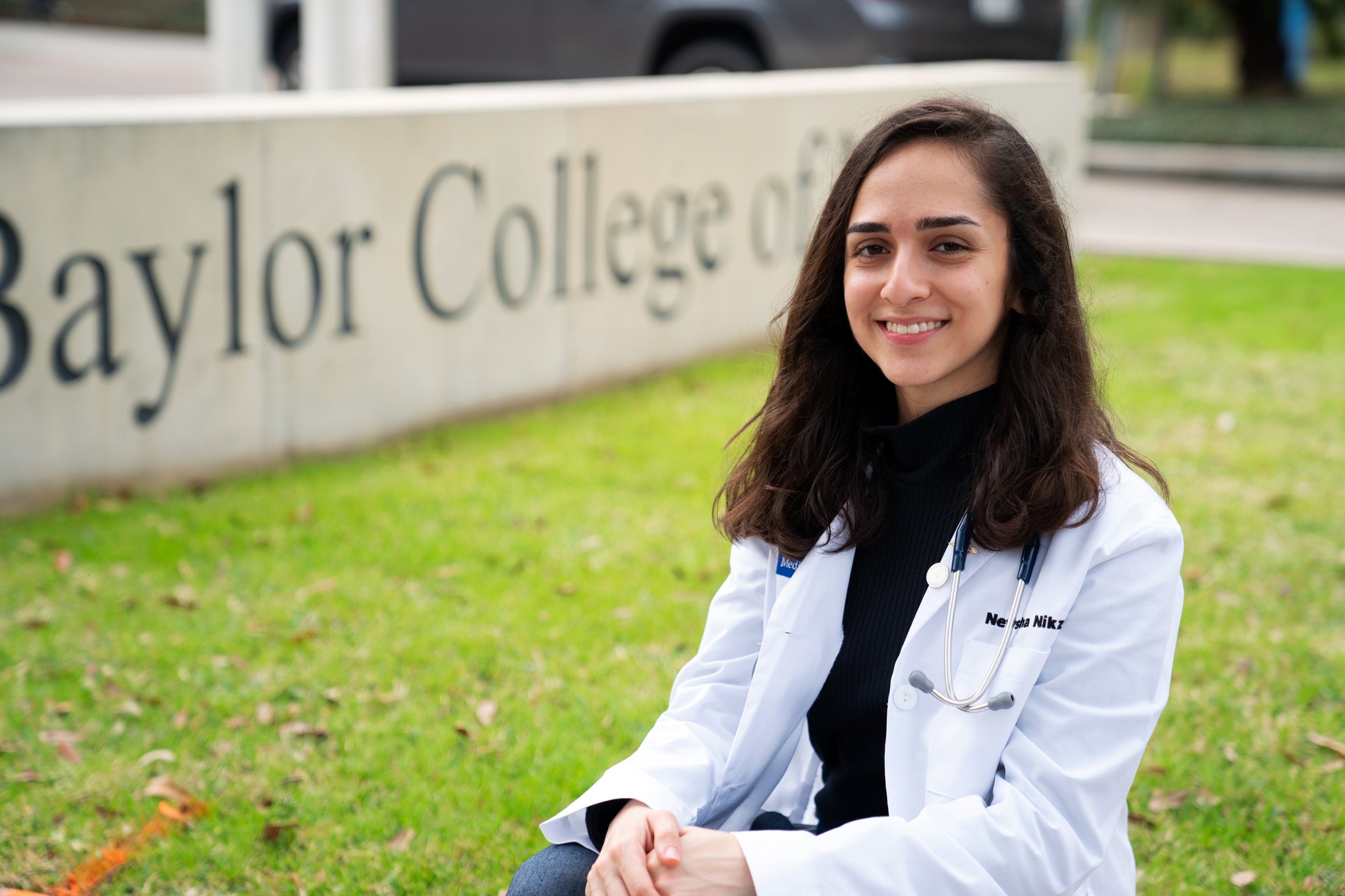

Any medical student’s first day of preceptorship is bound to be daunting even without screaming children awaiting them. When two shrieking young boys arrived at a Texas Children’s clinic with their Spanish-speaking mother, Newsha Nikzad was ready. That’s because in Rice’s Center for Languages and Intercultural Communication (CLIC) — where Nikzad had taken several courses in medical Spanish — language instruction is taught with real people in mind.

“Medicine is a very humanistic practice,” says the Class of 2019 graduate. “When there's a language barrier, a huge part of the human connection is lost. Being able to speak a language that your patient or a member of their family speaks helps you in providing the best care possible.”

Nikzad, an alumna of Wiess College, entered Rice with medical school firmly in her sights. When researching application prerequisites and noticing the prevalence of bilingual requirements, she decided to pursue Spanish, in addition to sports medicine kinesiology, during the spring semester of her freshman year.

According to her former professor, CLIC associate director Luziris Pineda Turi, Nikzad excelled both in language proficiency and cultural understanding. “As I started to discuss higher-level thinking topics in class, I started to notice that she had a very particular nuanced point of view,” she says.

“As I got to know her and learn that she herself is multicultural, already speaks another language that is not English, and understands what it means to be ‘othered’ within a U.S. context, her particular and natural ability made sense," says Pineda Turi. “Newsha had that critical eye to think about these situations with Spanish speaking patients.”

As part of her medical Spanish studies, Nikzad was an apprentice interpreter at the San Jose Clinic in downtown Houston, which serves communities with limited access to health care. “I could see that just trying makes a huge difference for the patients,” she says. “They like when you say ‘hola’ or ‘buenos días’ when they walk in instead of, ‘Let me go get another interpreter for you.’”

As minor as a slight shift in tone or the use of one phrase over another may seem, Nikzad says that learning to make those choices was one of the most essential lessons in her medical Spanish studies. “When you're interacting with a patient and you use terms that the patient prefers, the way that they respond to you is more positive and they're more receptive to things that you're telling them they need to be doing to improve their health,” she says.

This focus on cultural proficiency, awareness, and sensitivity in medical settings formed when Pineda Turi and her colleagues noticed a national landscape in which health and humanities are becoming increasingly intertwined.

“Most medical students will have all the scientific knowledge checked off — that they’ve worked in a lab, for example — but it’s important that they add other elements as well like engaging with the community, working with patients of all different backgrounds and speaking another language.”

Pineda Turi believes the goal of medical Spanish is similar to that of the School of Humanities’ medical humanities program: “to provide our students with broader knowledge beyond the scientific.”

The demand for intercultural competency in the medical field influenced Pineda Turi and her colleagues to move beyond terminology-focused curriculum. “We knew we had to challenge students beyond technical vocabulary,” she says. “A student could be grammatically perfect, go through set questions with a patient but they might lack the critical knowledge of what it means to be Latinx and not speak the mainstream language of health care here in the United States.

“We are able to bring that into the conversation and say, ‘Yes, we’re going to give you the language that you need and you're going to be proficient as an advanced speaker, but you need to add the intercultural aspect in order to be able to successfully interact with patients of different backgrounds,’” she says.

Even before venturing to a place like San Jose Clinic, medical Spanish students come remarkably close to real patient interaction inside the classroom thanks to an extensive database of physician-patient interactions that CLIC faculty recorded and transcribed. By comparing the real-world interactions with artificial dialogue from textbooks, students become sensitive to the cultural cues that come into play in real medical settings. They are also trained and assessed through role-plays with real medical prompts.

“Your patients do not follow a formula and they don't fit into what the textbook presents you. It’s our responsibility to be really flexible in how we approach each situation,” says Nikzad. “Having that mindset is something that has been incredibly valuable at Baylor. I didn't have to start from scratch when it came to practicing that on a day-to-day basis in the classroom and in the clinic.”

On the first day at her preceptor site, Nikzad felt all of her medical Spanish experience come full circle. “It was by far one of the most challenging and rewarding things I've experienced so far,” she says.

Afterward, she penned a note to her former professor Pineda Turi: “Everything that you have spent years teaching me just came through in that one experience that I had with those patients and their mom. And I can't thank you enough for giving me the skills and strength to go ahead and do what I was supposed to do effectively.’”