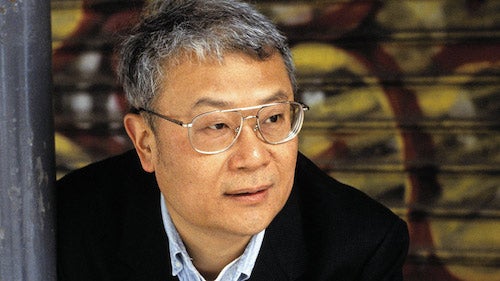

Acclaimed author Ha Jin intended to return to China after he earned his Ph.D. in English at Brandeis University so he could pursue a teaching career and raise his family. But then life threw him a curve: the Tiananmen Square massacre. He decided it would be impossible to return to China because he would not be able to write with integrity there. His life as an expatriate — and his journey as a writer — had begun.

Jin discussed the challenges and opportunities of this journey that he and other writers who migrate to another country must face during last week’s Campbell Lecture Series at Rice titled “The Writer as a Migrant.”

Jin said writers like Soviet author Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Chinese author Lin Yutang, who established themselves in their native countries before their emigration to America, feel the need to become spokesmen on behalf of their people.

“Writers from less-developed countries are apt to define themselves in their social roles,” Jin said, “partly because of their guilt for their emigrations to the materially privileged West, and partly because of the education they received in their native lands, where the collective is held above the individual.”

Jin said in these roles, however, Solzhenitsyn’s and Lin’s work did not match the “artistic vigor” of their earlier fiction; it was their lasting literary works, not their social writings, that enabled them to “return” to their homeland.

“Their social functions in their lifetimes have been forgotten, and what remains are only the books secreted from their writing selves,” he said. “Only literature can penetrate the historical, political and linguistic barriers and reach the readership that includes the people of the writer’s tribe.”

Migrant writers have another choice in their journey: to write in their native language or in their adopted language. Jin said they already feel guilty about leaving their country but “the ultimate betrayal is to choose to write in another language.”

Jin said it took him a year to decide to write in English, and he did so to survive. He had to compete for university teaching jobs, and writing in English would be best for his family and his future in America.

Both Joseph Conrad, who migrated from Poland to England, and Vladimir Nabokov, who was exiled from Russia, chose to write in English for similar reasons. Jin said despite their “linguistic betrayal,” their literary works helped them become respected figures in their native countries.

Jin said this is because their work is universally translatable — their stories remain meaningful to people regardless of the language into which they are translated.

Migrant writers also have to cope with nostalgia for their homeland, the idea that they’ll someday return and the belief that their writing success is appreciated by the people of their homeland.

Invoking C.P. Cavafy’s poem “Ithaka,” in which Ithaka symbolizes arrival, not return, Jin said, “Since most of us cannot go home again, we have to look for our own Ithakas and try to find ways to get there.”

Jin presented three original lectures for the Campbell series, and they will be compiled into a book to be published by the University of Chicago Press. A video recording of the lectures also will be available in Fondren Library.

Past Campbell Lectures

The Campbell Lecture Series is organized by the School of Humanities and Arts Dean’s Office, with generous support from the Campbell Foundation. The mission of the lecture series is to bring distinguished scholars in the arts, literature and humanities to Rice to discuss their work and career, while supporting engagement between scholar and student.