My concerns in these three lectures are Shakespeare’s sense of freedom; his sense of beauty; and his sense of hatred.

Shakespeare was fascinated throughout his career by the dream of autonomy. Many of his most memorable and compelling characters lay claim to the ability to live by their own laws. He was fascinated too by the particular extension of this claim to artists and their creations. “Only the poet,” Shakespeare’s contemporary Sir Philip Sidney wrote, goes “hand in hand with nature, not enclosed within the narrow warrant of her gifts, but freely ranging only within the zodiac of his own wit.” But, as we will see, both the conditions of the theater in which he worked and his own moral understanding led Shakespeare to articulate grave reservations about such freedom.

Shakespeare understood his art to be dependent upon a social agreement, but he did not simply submit to the norms of his age. Rather, as I will argue, he at once embraced those norms and subverted them. My focus for exploring this subversive embrace is Shakespeare’s response to his culture’s ideal of beauty, radiant, flawless, unmarked by time and accident. The plays and the sonnets repeatedly endorse this ideal, while at the same time finding an unexpected, paradoxical beauty in the marks, stains, scars, and wrinkles that had figured in the Renaissance only as signs of ugliness, disgrace, and difference. That paradoxical beauty was for Shakespeare bound up with what it meant to be a distinct and unique individual.

My focus in the third lecture will be on this individuality, and I will begin by observing the disturbing fact that in Shakespeare’s work the dream of absolute individuation and the dream of absolute freedom repeatedly fuse in implacable, murderous hatred. Shakespeare first glimpsed this fusion in Titus Andronicus’s black villain, Aaron the Moor, and in the crook-backed Richard III. His great artistic breakthrough was in the haunting figure of the Jew, Shylock, whose desire to destroy marks an emergence into full, complex individuality. But there are limits to Shylock’s hatred: after all, he wishes to kill his enemy and yet remain within the law. Some years after The Merchant of Venice Shakespeare returned to the problem of hatred and imagined a figure for whom there were no limits. He gave his character the qualities of a demonic artist -- a cunning playwright willing to stop at nothing in order to construct the perfect plot – and called him Iago.

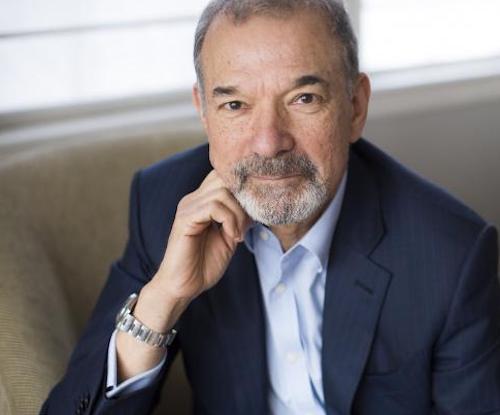

Stephen Greenblatt is Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. Founder of the "new historicism," Greenblatt is a specialist in Shakespeare, sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English literature, the literature of travel and exploration, and literary theory. Former president of the Modern Language Association, he is also a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society and a permanent fellow of the Institute for Advanced Study in Berlin. Greenblatt is the author and editor of numerous books, including Will in the World (2004; a New York Times Best Seller), Hamlet in Purgatory (2001), The Norton Anthology of English Literature (general editor, 2006). Recipient of the Mellon Distinguished Humanist Award, his research has been supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Guggenheim, Fulbright, the American Council of Learned Societies, and other funding agencies.

Past Campbell Lectures

The Campbell Lecture Series is organized by the School of Humanities and Arts Dean’s Office, with generous support from the Campbell Foundation. The mission of the lecture series is to bring distinguished scholars in the arts, literature and humanities to Rice to discuss their work and career, while supporting engagement between scholar and student.