Despite its obsolescence, small-town America remains an important imaginary place that continues to supply that “dreamy idea of Americans as a people who are so fortunate that we can feel immune to the past, oblivious or blind to dark historical realities, like slavery, and equally blind to dark realities in human nature.”

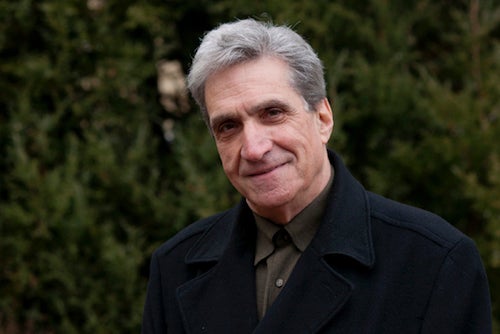

Former U.S. poet laureate Robert Pinsky offered this assessment of “the town” in the inaugural Campbell Lecture Series at Rice University last week.

In “The American Town: Dreams and Nightmares,” the author gave three original lectures, re-examining Americans’ nostalgia for the small town and discussing seven works that epitomize the small town as Americans think of it: Mark Twain’s “Pudd’nhead Wilson,” William Faulkner’s “The Hamlet,” Thornton Wilder’s

“Our Town,” Willa Cather’s “Song of the Lark” and three films, “Shadow of a Doubt,” directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and “Miracle of Morgan’s Creek” and “Hail the Conquering Hero,” both directed by Preston Sturges.

The towns in these works, created during the early and middle part of the 20th century, when “the reality and myth of the small town occupied artists and authors at many levels of ambition,” reflect an idyllic place of innocence, purity and warmth that exists in a bubble of isolation, Pinsky said. Cut off from history or from the rest of the world, they are untouched, quiet, unchanged and unchanging.

But the town’s “innocence is as illusory as its stasis,” Pinsky said, and the bubble bursts when an outside force enters — a stranger to the town who reveals that it indeed has been a part of this history, part of the larger world. He makes visible to the town its blind participation in such things as corruption, slavery and war.

Pinsky said blindness is a consistent theme across these stories — blindness to change, to injustice, to human relationships — and is not completely unlike the illusions people create for themselves, whether intentionally or innocently, about their own small-town experiences.

“We make up stories about our places, and sometimes we make up considerable proportions of the places themselves,” he said. “The invention may be a form of fantasy, rooted in dread or desire or, in the terms of my lecture’s title, rooted in nightmares and dreams,” he said.

“The partly legendary town of these writers and filmmakers has been an enduring central repository for larger hopes as dreamy as the flowery streets of [Twain’s] Dawson’s Landing and fears as terrible as lynchings,” Pinsky said.

Americans tend to be nostalgic for the small town and the good old days, but Pinsky said poetry, literature and film can transport us from that nostalgia to a deeper sense of loss, and an examination of the works raises disturbing questions about the so-called simplicity of the small town.

The idea of a place where everyone recognizes one another and knows one another extensively or even intimately seems “a wonderful palliative for the anonymity and alienation of modern life,” he said. But that same place can become a suffocating provinciality.

The reality of the idealized town offers constructive guidance for people as individuals and as a nation. “One of the most important tasks of American life is figuring out how to relate humanly to one another,” he said.

Pinsky’s lectures will be compiled into a book to be published by the University of Chicago Press, and a tape of the lectures will be available in Fondren Library.

The three-day presentation launched the Campell Lecture Series, established with a $1 million endowment from alumnus T.C. Campbell ’34. The School of Humanities and Campbell collaborated over the past year to create a series that would support both parties’ commitment to the study of literature. The end result is an annual 20-year lecture series that will be open to the public and present original ideas on topics of interest in literature.

A community advisory committee, chaired by Dean of the School of Humanities Gary Wihl, organized the activities of the lecture series and includes Robert Patten, the Lynette S. Autrey Professor in Humanities at Rice; Karl Kilian, owner of Brazos Bookstore; Rich Levy, executive director of Inprint; James Gibbons, a member of the Houston Chronicle editorial board; and Edward Hirsch, president of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation.

Past Campbell Lectures

The Campbell Lecture Series is organized by the School of Humanities and Arts Dean’s Office, with generous support from the Campbell Foundation. The mission of the lecture series is to bring distinguished scholars in the arts, literature and humanities to Rice to discuss their work and career, while supporting engagement between scholar and student.